Informing Transition from Food Delivery to Food Vouchers in Indonesia

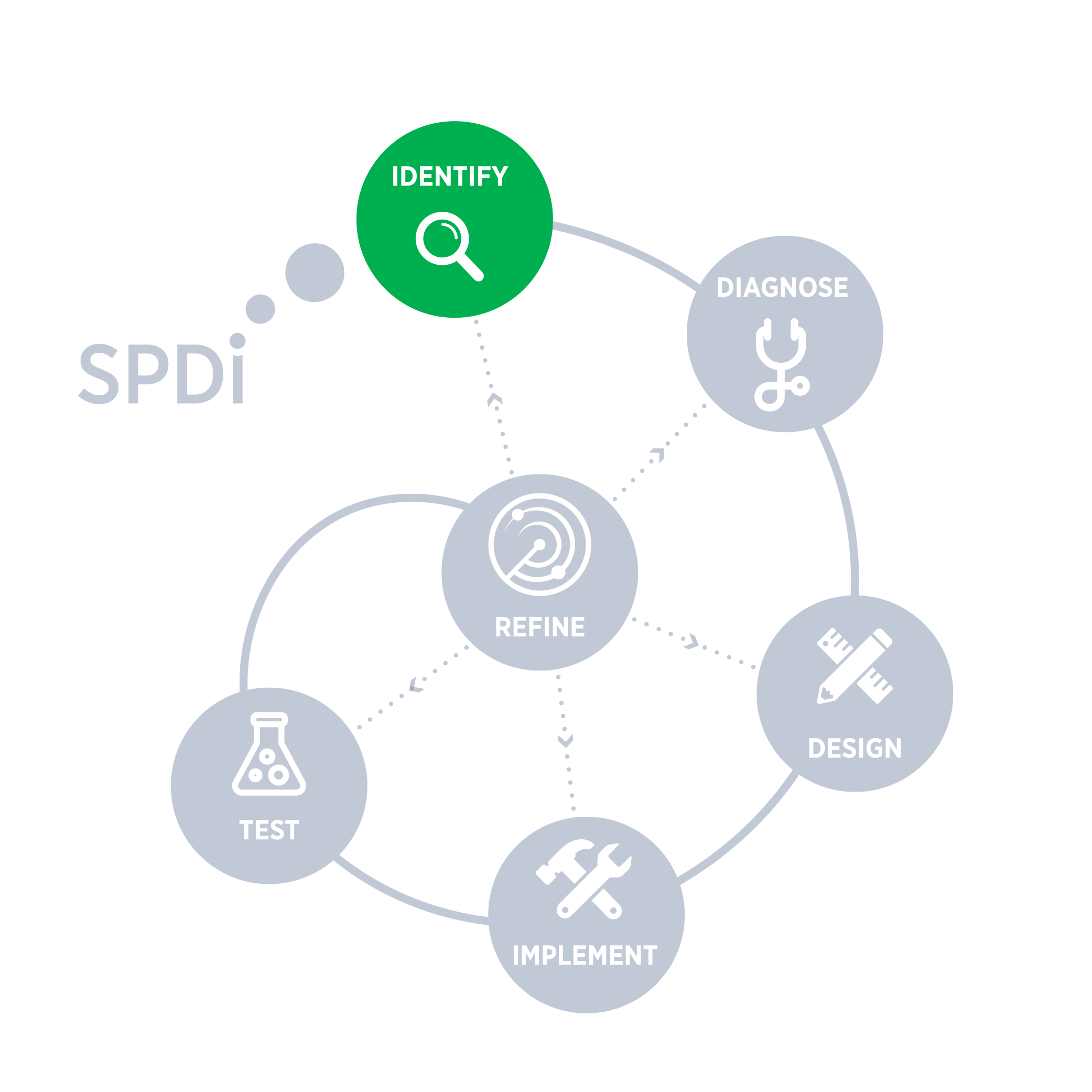

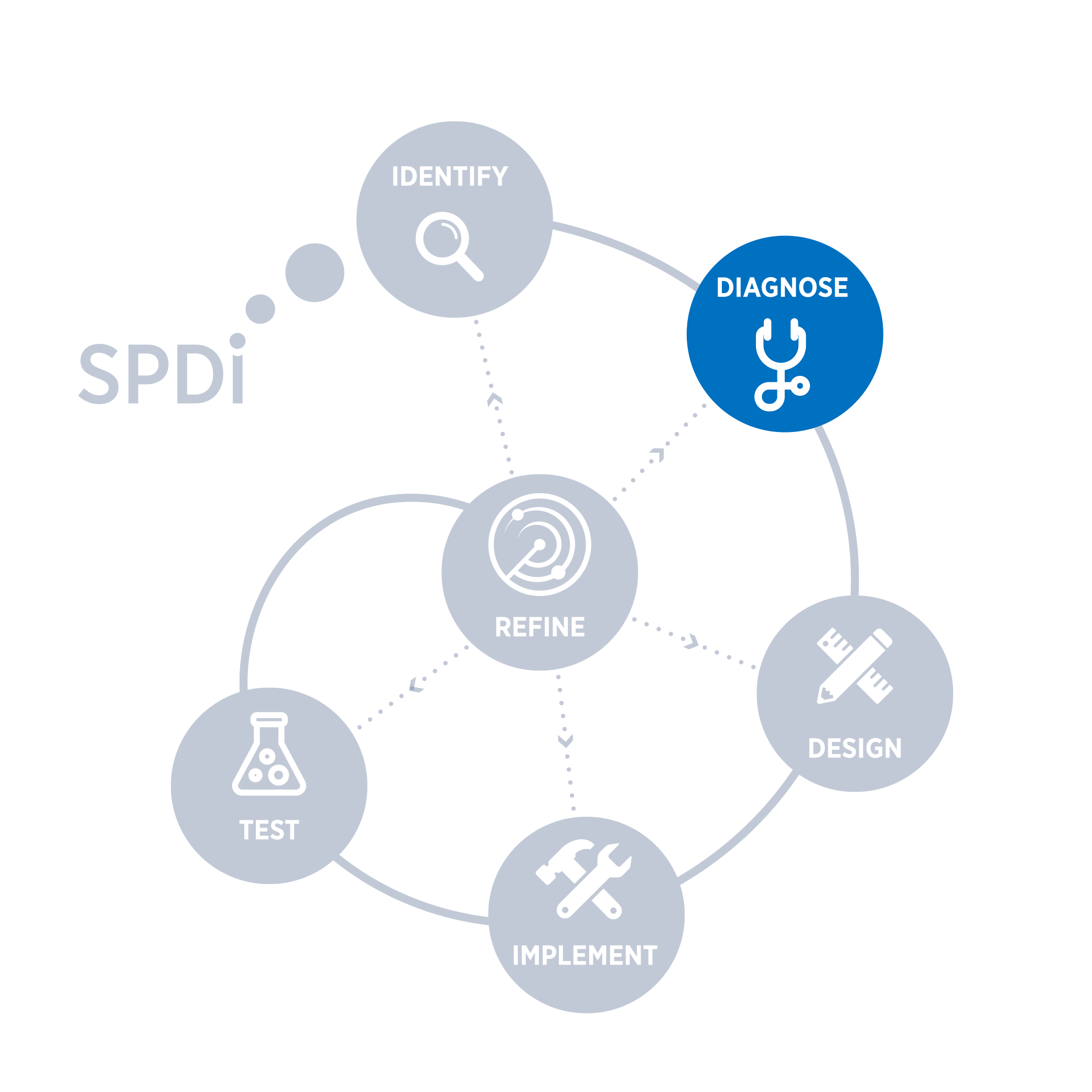

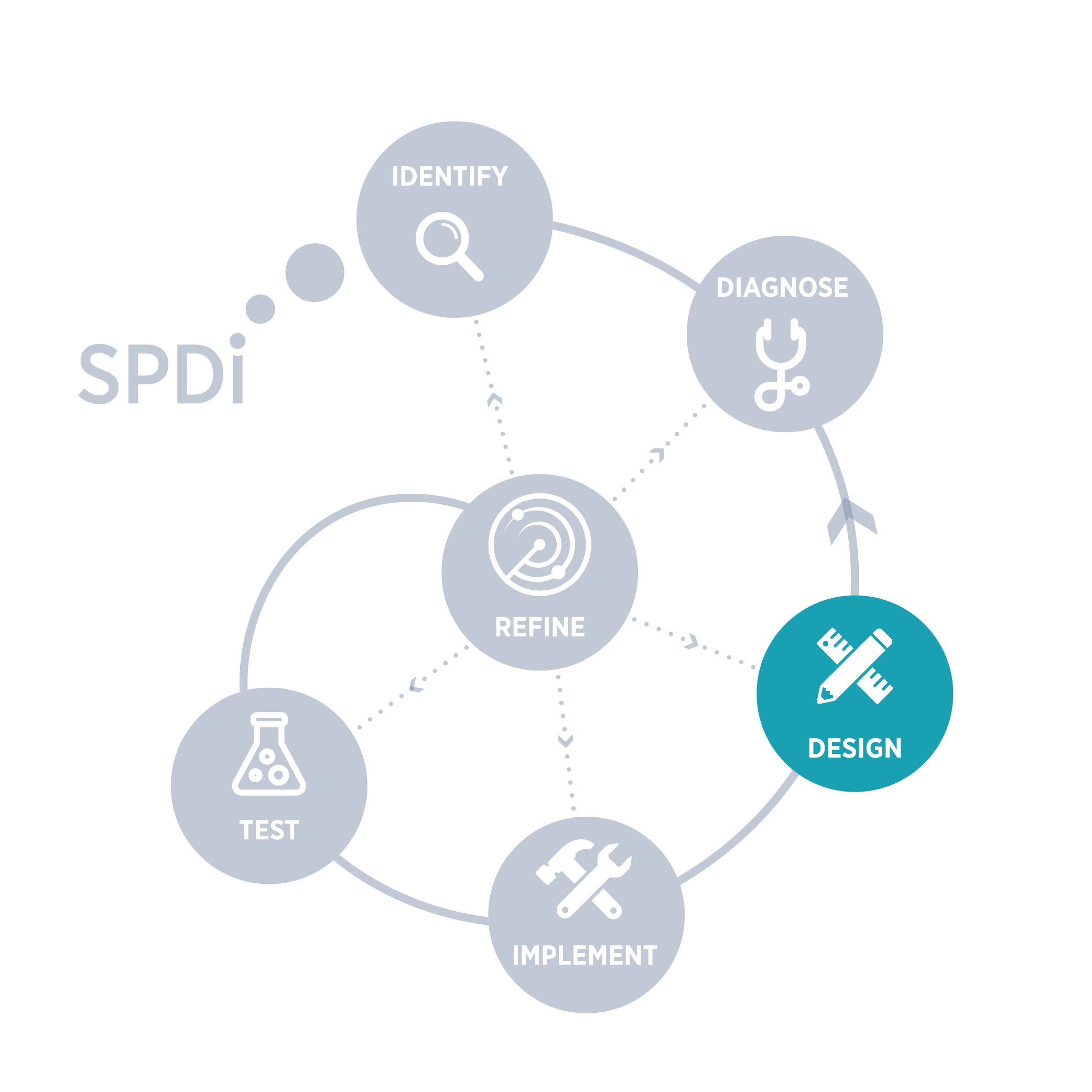

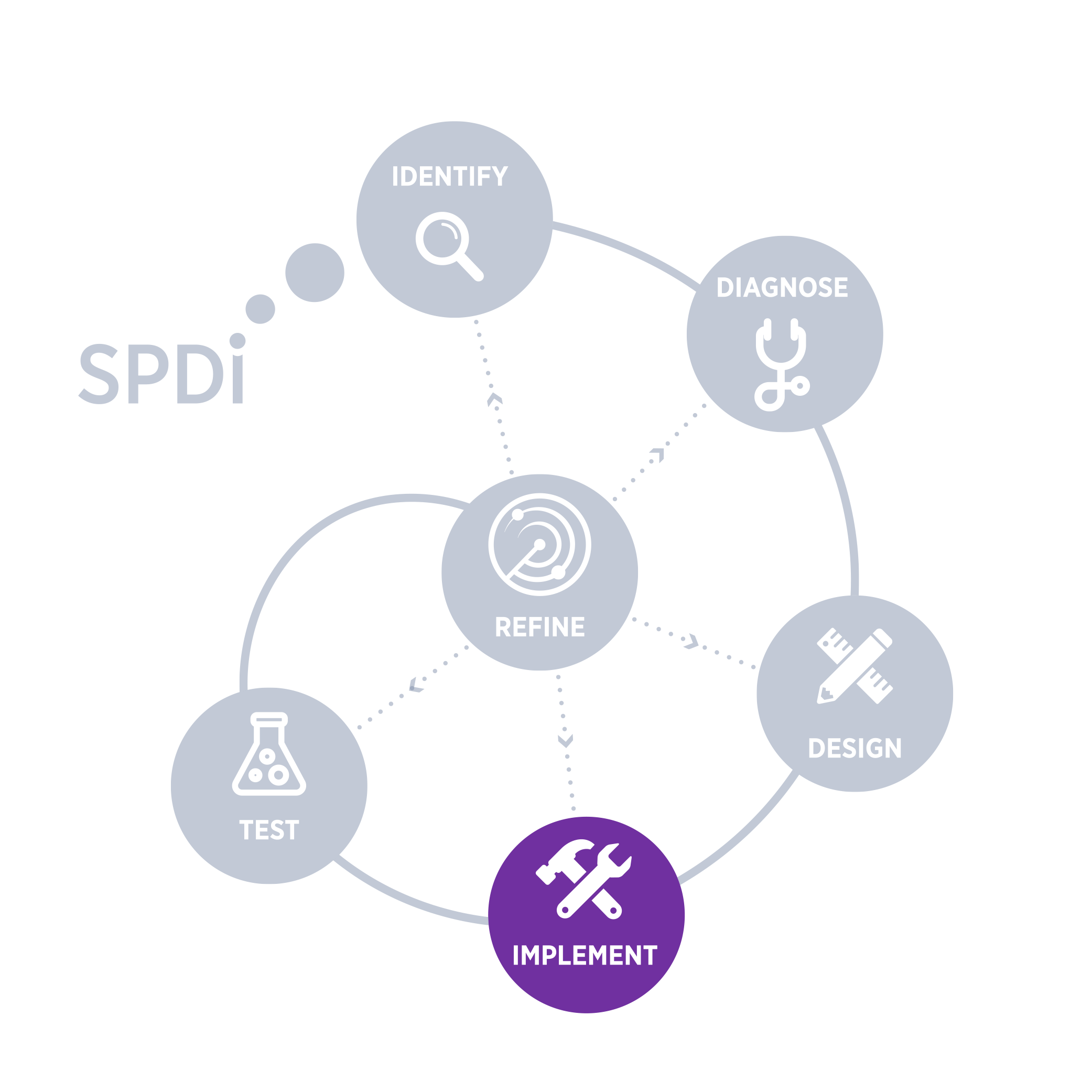

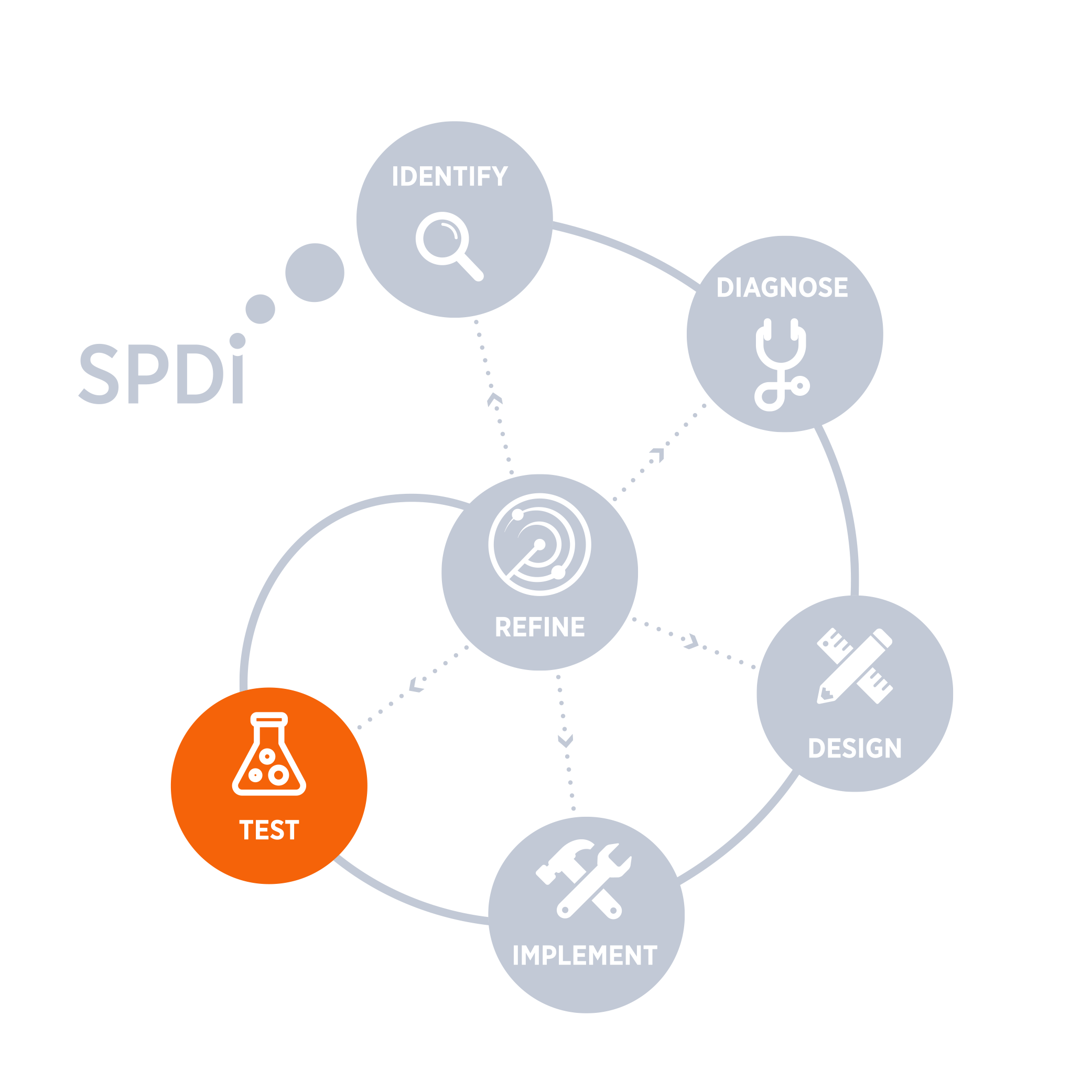

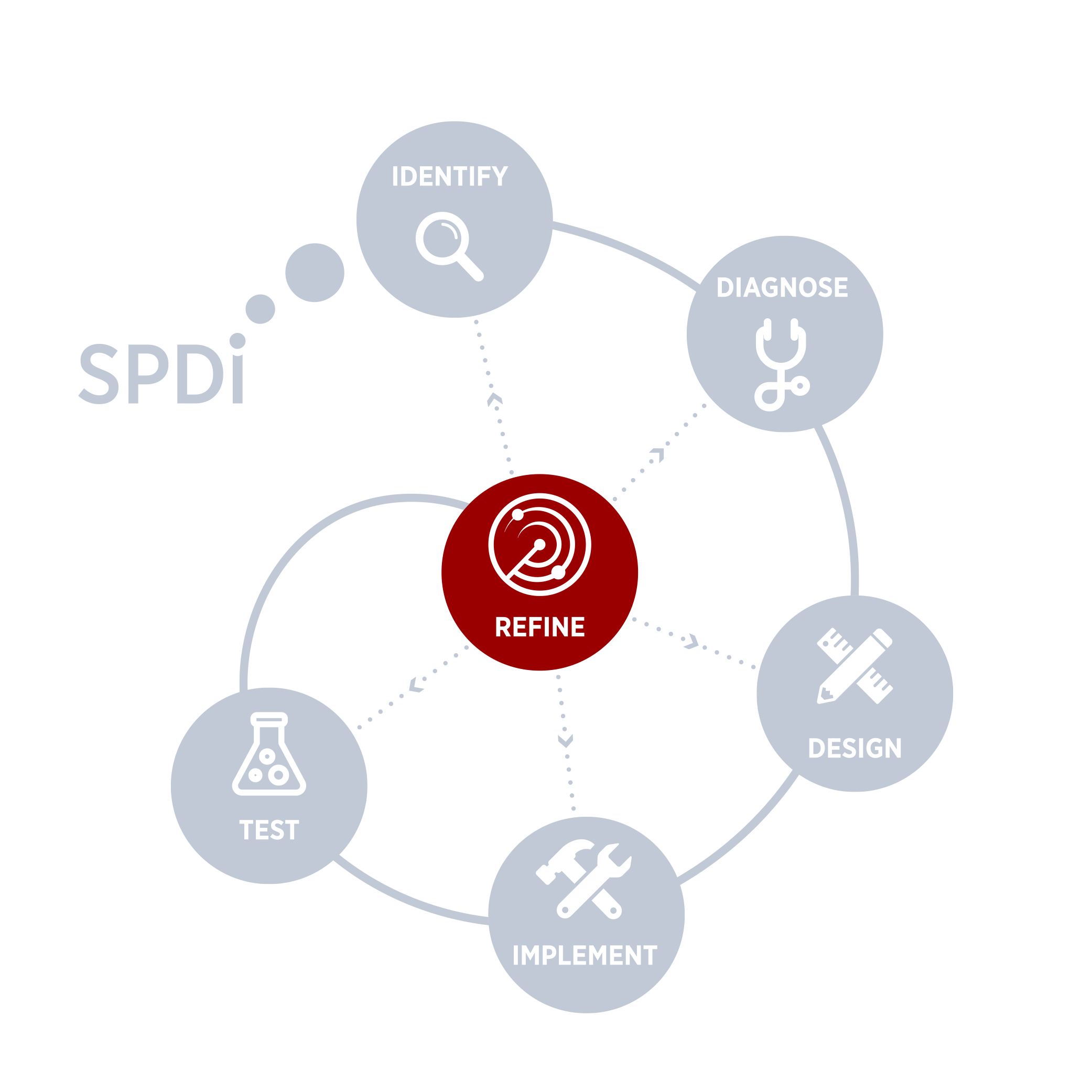

What is the difference in impact between welfare programs that provide food vs. programs that provide food-vouchers? Researchers affiliated with Evidence for Policy Design (EPoD) at Harvard Kennedy School and the Abdul Latif Jameel Poverty Action Lab (J-PAL) sought to answer this question based on the Indonesian government’s largest social assistance program, Rastra (formerly called Raskin). The program provides 10 kg of rice to the bottom 25 percent of Indonesia’s income distribution, and the Government of Indonesia randomly phased the transition from in-kind delivery to equivalent electronic vouchers. Using the SPDI approach, researchers accompanied the transition and evaluated program effectiveness and also relative delivery costs. Read below about how this research informed the transition of what became a key part of Indonesia’s social safety net during the COVID-19 pandemic.